Cloudflare announced Stream Live for open beta in 2021, and in 2022 we went GA. While we talked about the experience of using it and the value it delivers to customers, we didn’t talk about how we built it. So let’s talk about Stream Live’s design, and how it leverages the distributed nature of Cloudflare’s network, rather than centralized locations as many other live services do. Ultimately, our goals are to keep our content ingest as close to broadcasters as possible, our content delivery as close to viewers as possible, and to retain our ability to handle unexpected use cases.

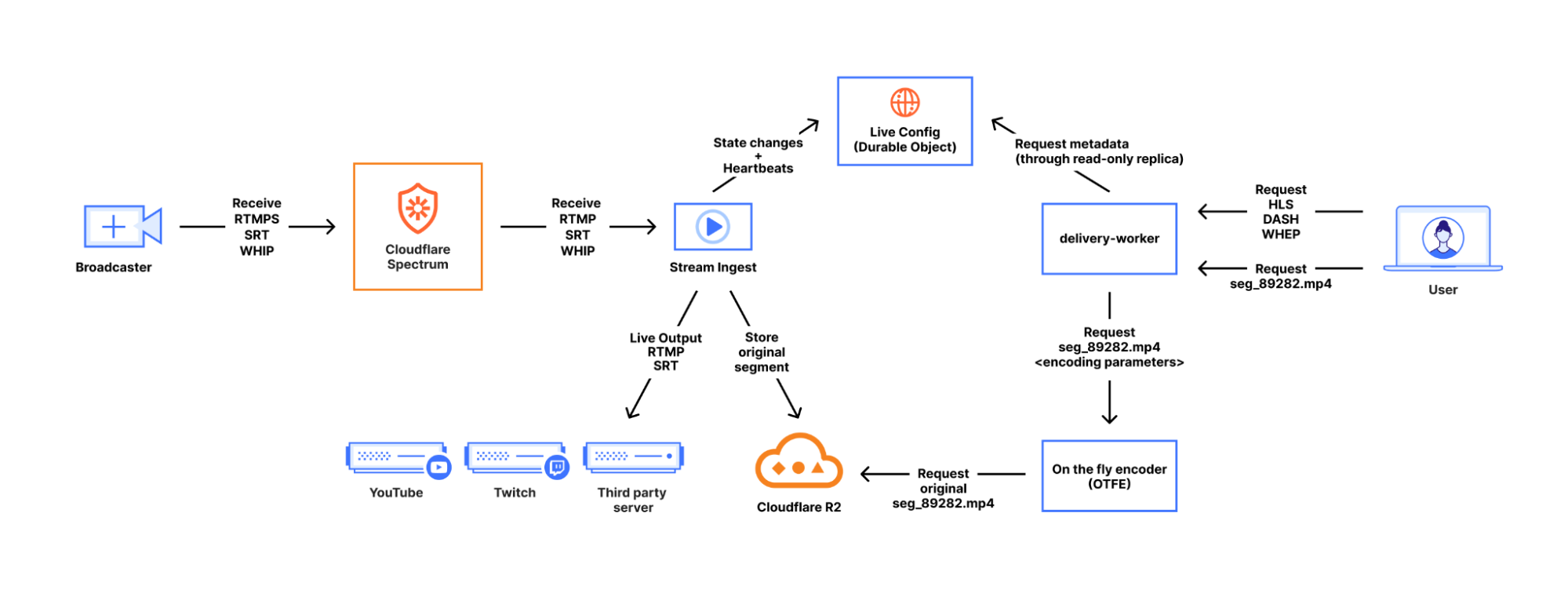

At a high level, Stream Live accepts audio/video content from broadcasters and makes that content available to viewers around the world in real time through the Cloudflare network, which reaches more than 330 cities in over 120 countries. Hence, there are two sides to this: ingesting data from broadcasters and delivering encoded content to viewers. Both sides are built on a combination of internal systems and Cloudflare products, including Cloudflare Workers, Durable Objects, Spectrum, and, of course, Cache.

Let’s start on the ingest side.

Ingesting a broadcast

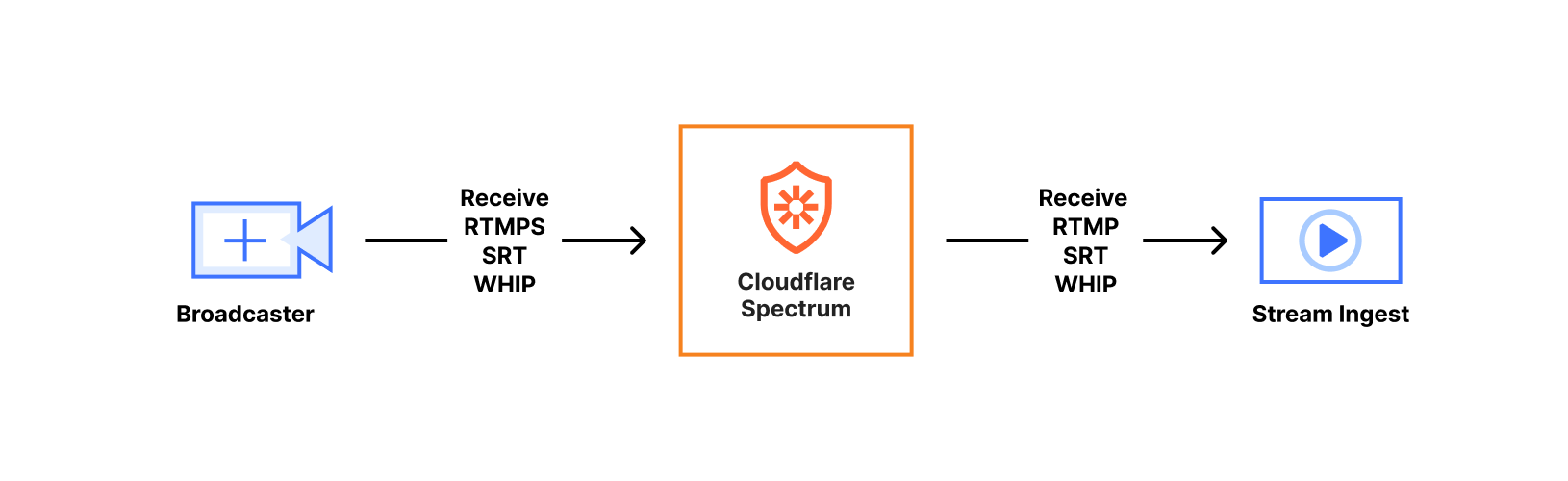

Broadcasters generate content in real time, as a series of video and audio frames, and it needs to be transmitted to Cloudflare over the Internet. To communicate with us, they choose a protocol such as RTMPS (Real Time Messaging Protocol Secure), SRT (Secure Reliable Transport), or WHIP (WebRTC-HTTP ingestion protocol) that defines how their content is packaged and transmitted. Each of these protocols is a way to transmit audio and video frames with various tradeoffs.

Regardless of the chosen protocol, the ingest lifecycle looks fairly similar. Broadcasters connect to an Anycast IP address using either a custom ingest domain or our default live.cloudflare.com. Both options direct to an IP address advertised from every Cloudflare data center around the world, minimizing the latency for broadcasters (both big and small) to our ingest points.

When the media content arrives at the Cloudflare server servicing the connection, it is first handled by a Spectrum application. Spectrum saved us time by implementing TLS termination for RTMPS, blocking potential DDOS attacks, and a few other protocol-specific benefits, such as our ability to support SRT broadcasters whose clients don’t support the Stream ID portion of the SRT protocol. Those broadcasters assume their connection can be fully identified by connecting to a specific port, which was a challenge for our multitenant service. We use Spectrum to expose many listening ports to specific broadcasters which get wrapped up in Simple Proxy Protocol and sent to one ingest service port. This is important, as our SRT implementation spends a non-trivial amount of CPU for each listening port, whereas Spectrum spends effectively nothing. In any case, Spectrum forwards all connections to the ingest service running on the same server.

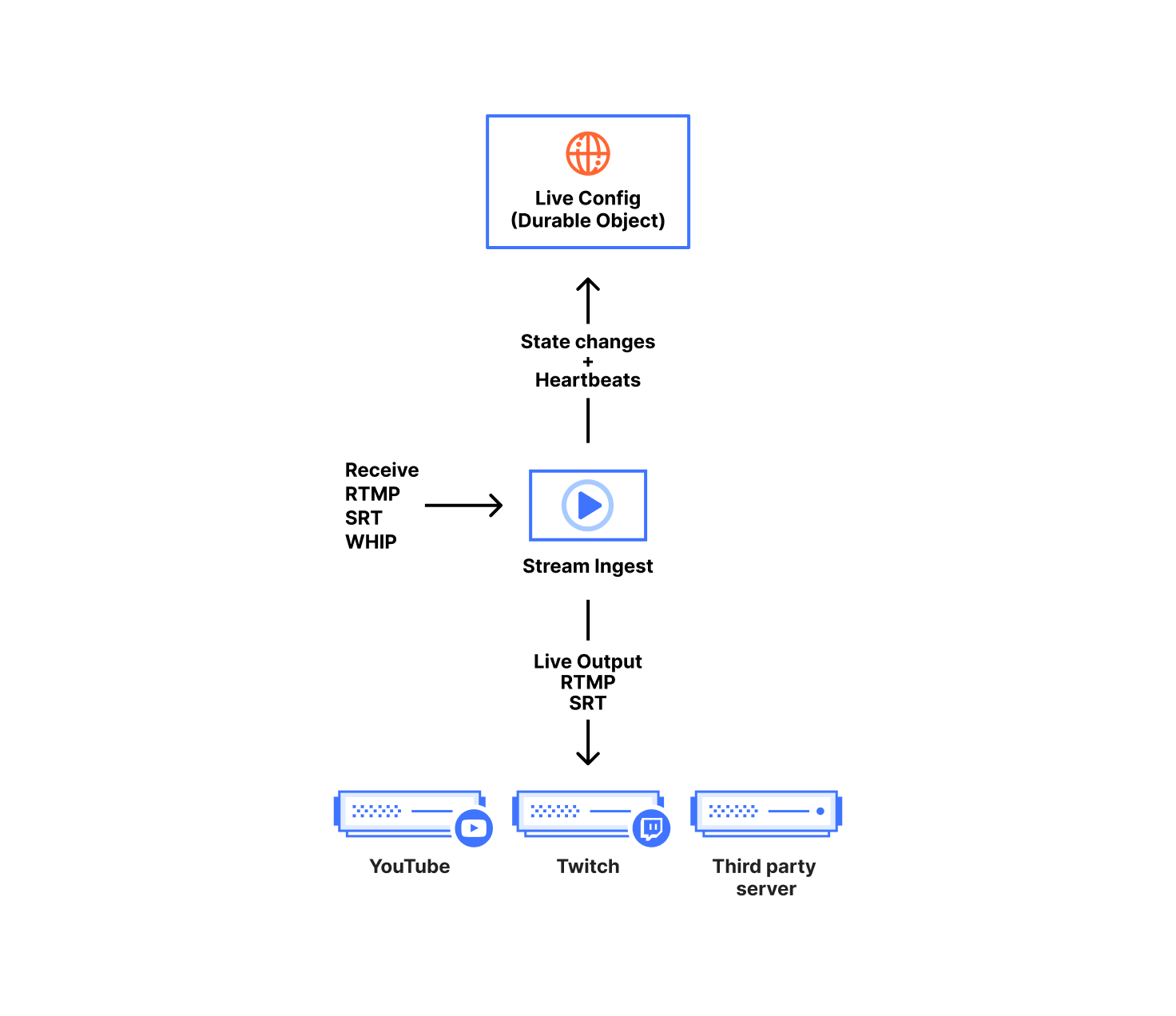

Our ingest service handles receiving content from broadcasters, forwarding to live outputs, and recording for HLS/DASH viewing. The ingest service is written in Go and acts on configuration and broadcast state stored in our Live Config Durable Objects. One Durable Object instance represents one live input; it contains both the customer configuration and the ongoing state of each broadcast.

We chose Durable Objects over a centralized database since they are not coupled to any specific data center, allowing them to be closer to each of our geographically distributed broadcasters while remaining highly available. In terms of customer configuration, we use Durable Objects to store everything defined when creating or modifying the live input.

We store the canonical state of the broadcast in the Durable Object. That includes timestamp metadata for keeping times monotonic, connection status, and which ingest service instance owns the broadcast. Any content received by the ingest service needs to be acknowledged and indexed by the Durable Object before it is made available to viewers. This splits our state into two types, ‘volatile’ and ‘committed’. Volatile state is content the ingest has received but not yet told the Durable Object about. Committed state is content the Durable Object has acknowledged and is used as a sync point for any other ingest service instance in the event they claim ownership of the broadcast.

This split between volatile and committed states is how we support broadcasters resuming a live broadcast after disconnecting and reconnecting for whatever reason, including a broadcaster network blip. That’s normally a relatively easy problem when you have centralized ingestion and state storage. Since broadcasters connect to an arbitrary server due to Anycast, we needed to get more creative in making sure that whichever server receives the reconnect has the data to continue the broadcast.

The ingest service itself is written as a relay, taking packets from one input stream and mapping them to multiple output streams. At the top level, the relay is implemented as two coupled ‘for’ loops that communicate over a Go channel, one for sending and one for receiving. When we receive data, we internally normalize it depending on the protocol. For example, some protocols send video packets as delimiter-based (annex B h264 NALU), but other protocols or file formats expect length-prefixed packets (avcc h264 NALU).

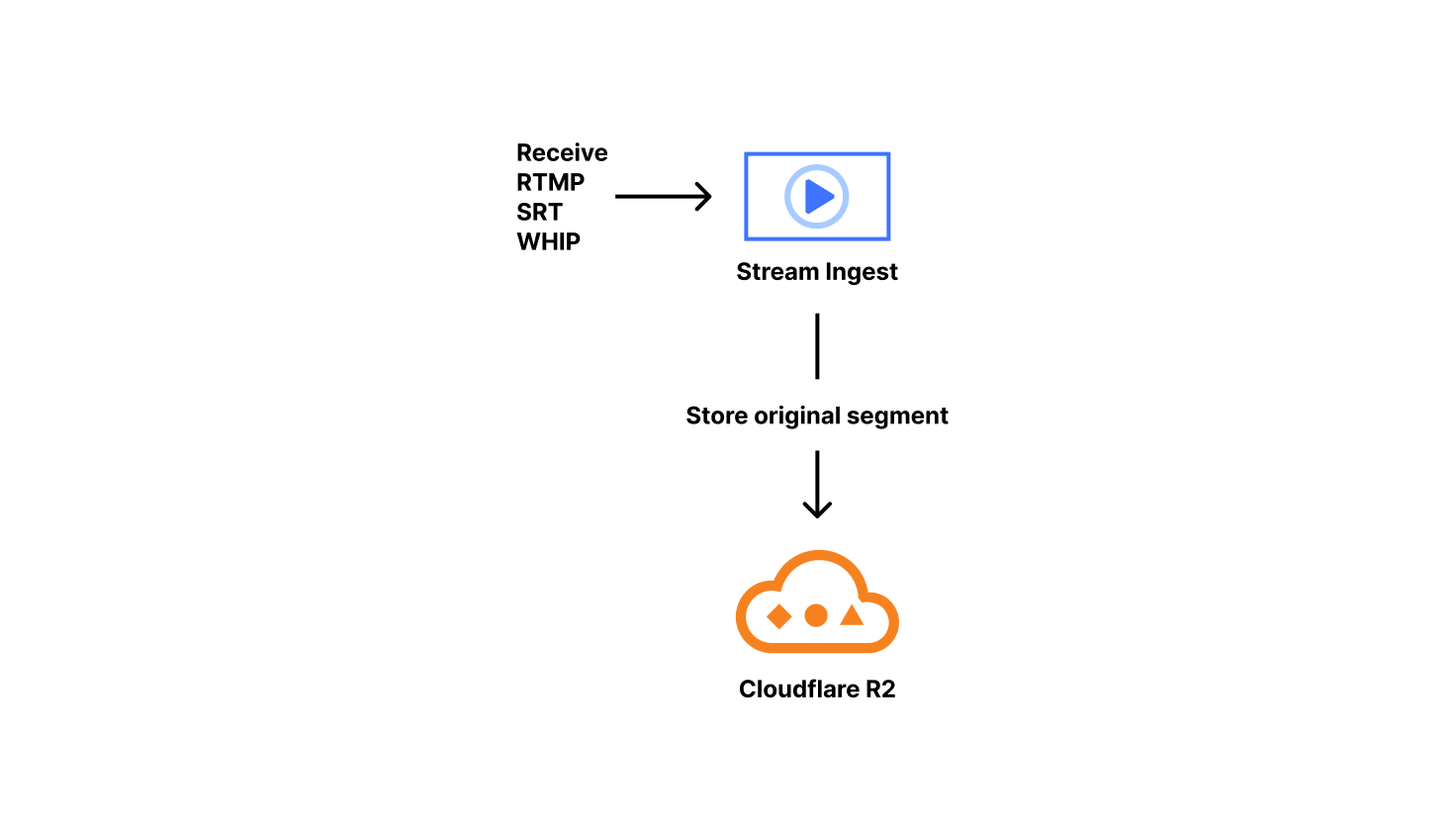

A special case of relay outputs is our Live Playback and Recording functionality. When this is enabled, we copy and sanitize the incoming packets. Specifically, we issue monotonically increasing timestamps, which solves many issues we’ve encountered with various customer encoders. To ensure everything is aligned, we drop severely misaligned audio/video blocks, something typically seen at the start of broadcasts. Those sanitized packets are packaged into fragmented MP4s on keyframe boundaries. We call those fragmented MP4s ‘original segments.’ Our ingest service stores the original segments in R2 and lets the live config Durable Object know the segment exists and how long it is.

These original segments are considered the canonical copy of the content a customer has uploaded to us, and are reused when transitioning from live to on-demand. Since these are required to serve live viewers, this is why we don’t currently provide an option to decouple live playback from recording. Supporting live playback automatically implements on-demand recording, with some state management overhead.

Viewing the broadcast

At this point, we’ve ingested the content, cleaned it up, and durably stored it. Lets talk about how viewers watch this content.

Most online video is delivered in short ‘segments’, multi-second chunks of content. Splitting the output allows content to be progressively emitted and is very cache-friendly. The protocols viewers use to request that content are typically HLS (HTTP Live Streaming) or MPEG-DASH (Dynamic Adaptive Streaming over HTTP). WHEP (WebRTC-HTTP Egress Protocol) is a non-segmented viewing method available for real-time viewing in some cases. However, we’ll focus here on playback using segmented content with HLS or DASH, since that’s most of Stream Live’s usage today.

To start viewing, a video player will request an HLS or DASH playlist which describes the attributes of the media content and acts as an index for each segment. The playlist tells us which segments map to what point of the video’s timeline. Those segments are inserted into a playback buffer to be decoded and displayed by a client’s player. Examples here will use HLS, which is a newline delimited format. The typical alternative is DASH, which is XML based.

First, ‘primary’ playlists describe which renditions of the same content are available, as well as where to get their specific index files. Those renditions can vary in bitrate, codec, framerate, resolution, etc. If you’ve ever picked ‘1080p’ from a video player quality menu, the player knew those qualities were available using this or similar methods. When selecting quality automatically, players choose the best rendition for the viewing machine’s capabilities (such as the ability to decode a certain codec) and network constraints. We use an internal representation of tracks (what kind of content, i.e. video), renditions (content parameters, i.e. 1080p), and muxings (where to find that content, i.e. in R2 bucket N or OTFE with call M) to generate both HLS and DASH, as the two formats contain nearly the same data, except organized differently. Here’s a simplified example of a ‘multi-variant’ or ‘primary’ HLS playlist that Stream generated. It includes some annotations to explain the components.

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-VERSION:6

#EXT-X-INDEPENDENT-SEGMENTS

#EXT-X-MEDIA:TYPE=AUDIO,GROUP-ID="group_audio",NAME="original",LANGUAGE="en-0a76e0ad",DEFAULT=YES,AUTOSELECT=YES,URI="stream_2.m3u8" <- Audio track description + URL path

...

#EXT-X-STREAM-INF:RESOLUTION=426x240,CODECS="avc1.42c015,mp4a.40.2",BANDWIDTH=149084,AVERAGE-BANDWIDTH=145135,SCORE=1.0,FRAME-RATE=30.000,AUDIO="group_audio" <- description of variant contents

stream_1.m3u8 <- URL path to fetch variantSecond, ‘variant’ or ‘stream’ playlists contain a list of segments that can be downloaded and viewed for each rendition. These are used for both live and on-demand viewing. The difference is on-demand playlists contain a flag indicating no more content will be added to the index whereas live omits that flag to allow it to append content in future requests. As a result, you’ll see video players download M3U8 (HLS) or MPD (DASH) files approximately every 1–10 seconds when viewing a broadcast, looking for updated content.

#EXTM3U

#EXT-X-VERSION:6

#EXT-X-MEDIA-SEQUENCE:89281 <- Indicates position of sliding window

#EXT-X-TARGETDURATION:6

#EXT-X-MAP:URI=".../init.mp4" <- Initialization data

#EXTINF:4.000, <- How long the segment

.../seg_89281.mp4 <- Location of a segment

#EXTINF:4.000,

.../seg_89282.mp4

#EXTINF:4.000,

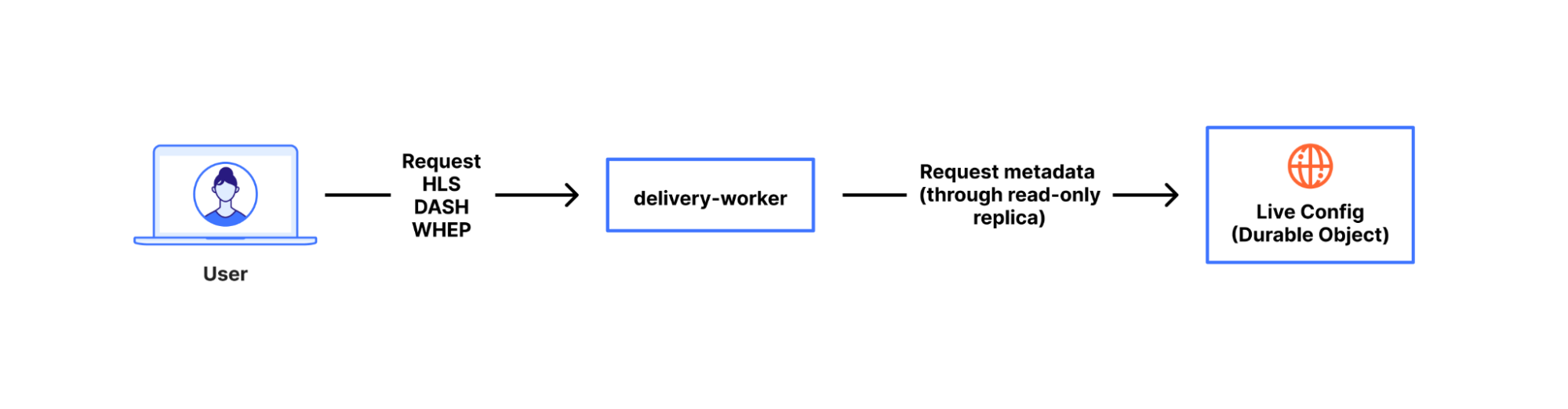

.../seg_89283.mp4To serve all requests from viewers, we use a Cloudflare Worker called ‘delivery-worker’. It handles all requests for Stream content, and had its first commit in 2017, making it one of the earliest production-facing workers at Cloudflare. Since it’s a worker that executes as close to a viewer as possible, it frees us up to spend more time on content and metadata performance rather than where our logic runs. It delivers content, renders playlists, and performs a variety of other functions. For rendering playlists, the worker transforms the broadcast state from the durable object, as mentioned earlier.

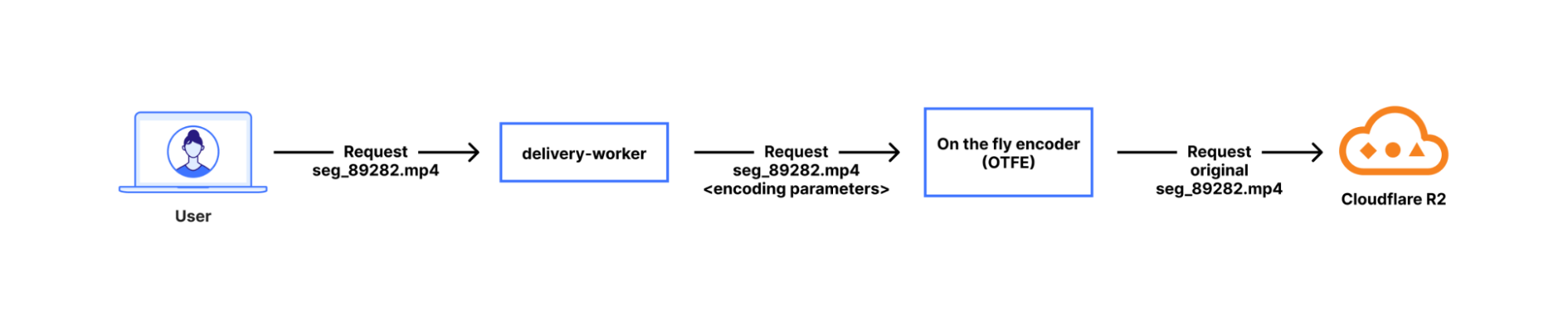

When clients ask for the encoded media content the playlist advertised to them, delivery-worker will send a subrequest to our OTFE (on-the-fly-encoder) service that transits the Cloudflare network. That request describes the format of content requested, i.e. the video stream of segment 89282 at a 1280×720 resolution encoded using AVC (aka H.264) capped CRF with some specified bitrate cap. Then, OTFE will encode the original segment to output the specified configuration.

On-the-fly encoding is more efficient than always-encoding, which is the approach most other platforms take. If there are no viewers watching a specific quality level, or watching the broadcast at all, then we aren’t encoding it. That saves power, CPU time, RAM, network, and cache space. Doing nothing is always more efficient than doing something. This applies to a variety of customer use cases, since not all broadcasts have many viewers widely distributed across a range of connection qualities. For one case, consider when serving live broadcasts that are primarily viewed on high quality connections — encoding 240p or 360p variants would probably go to waste most of the time. For a more extreme case, there are situations where you definitely want recording enabled for live content, but viewing is an exceptional situation, such as for security cameras or dashcams. Of course, we have many customers that have active viewership for their broadcasts and this architecture allows us to serve both use cases.

On-the-fly encoding has a tradeoff: it is hard to implement for “media-correctness” and performance reasons. Media-correctness is important to ensuring smooth playback; individual segments need to have exactly the right start time and duration, or you get stuttering playback, audio/video desync, or entirely unwatchable content. Perfecting our media output requires fine-tuning our encoding, deep-diving into specs, and adjusting fragmented MP4s — especially since most encoders aren’t designed for per-segment encoding. For performance, we hide encoding delay by aggressively prefetching segments from delivery-worker. When a viewer initiates a request for Segment N, we initiate encoding of segment N+1. Since that logic is implemented as a worker, we can also easily add or iterate the prefetching however we want.

This encoding flow stands on top of the Cloudflare network, which also provides us with tiered caching and request coalescing. Request coalescing is the key to supporting many viewers simultaneously but only encoding once by enforcing that, for any number of viewers requesting the same encoded content, only one of those requests will make it to our encoder origin — thanks to Cache.

That’s how Stream Live works at a high level. We ingest content from users, send it to any desired live outputs, transcode it for viewing, and give viewers a choice of quality levels, with a lot of backend complexity hidden behind a friendly API. All of this is built on top of the Cloudflare network, with Cloudflare as Customer Zero for our own products and services, using the same as the ones available to our customers.

There’s a lot more we can write about for problems we’ve solved in building Stream Live over the last few years, but those will have to be for a future blog post. If this mix of media and distributed system problems discussed here sound interesting, the Cloudflare Media Platform is hiring for several roles. Apply and join us!

Source:: CloudFlare