Within the Kraken platform, we leverage Amazon Web Services (AWS) streams to capture and ingest data changes from API databases. Consumers take these changes to fulfill other business requirements, which can be time sensitive to process. In this blog post, we outline how stream consumer performance is measured, as well as options we recently explored to reduce processing times.

Our investigation and performance improvements were recently undertaken whilst developing the Power API – a new API facilitating the read and write of dispatches for energy assets. In this context, an asset takes one of many forms, such as a large-scale commercial battery supporting national infrastructure like the National Grid in the UK, or an electric vehicle charging at a customer’s home. A dispatch is the import or export of power from the asset. For example, a commercial battery may export power to the National Grid at times of peak electricity demand.

The Kraken platform continues to grow – acquiring more assets, in particular electric vehicles, which must read and write dispatches to the Power API. Every time a dispatch is added or updated via the API, several other services critical to the Kraken platform must process these dispatch changes. For example, services responsible for generating asset instructions rely on the most up-to-date dispatch requests.

Kraken hosts its APIs in the cloud using AWS. Within the Control & Dispatch team, we own the Power API and follow a philosophy of adopting serverless technology where this benefits business needs. Therefore, we elected to use Amazon DynamoDB – a serverless NoSQL service – for the API’s data storage requirements.

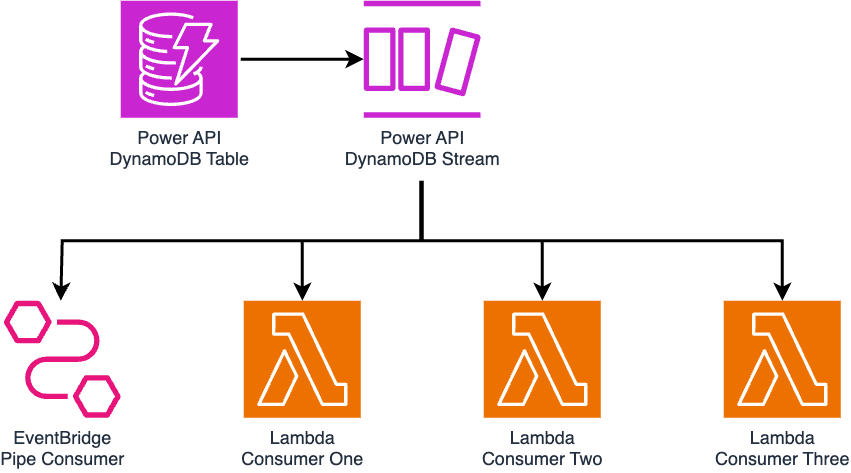

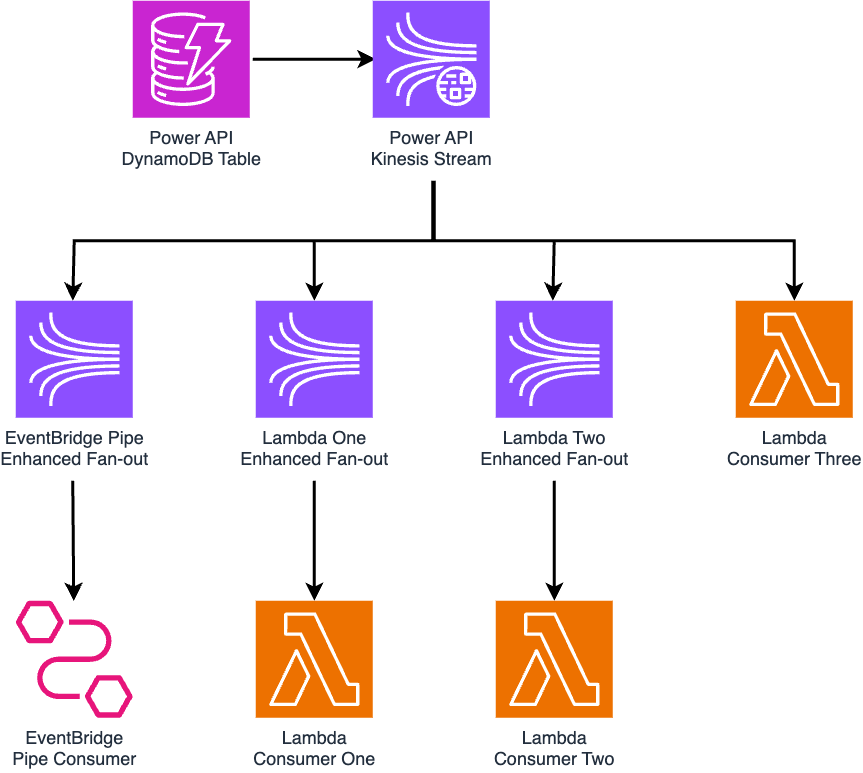

To capture and fan-out dispatch changes from DynamoDB, we leveraged DynamoDB Streams: a stream integration managed by AWS which records data inserted, updated, and deleted from the DynamoDB table. Services that must process dispatch changes may synchronously consume stream records, analyze what data has changed, and act accordingly on those changes. For Power API, four services were set up to consume DynamoDB Stream records: one EventBridge Pipe – explored in a previous Kraken Tech blog post – and three Lambda functions.

Before going live with Power API, we wanted to measure system performance and explore where improvements may be possible to reduce processing times. In the case of our DynamoDB Stream, we wanted to understand how quickly consumers successfully processed a record after it’s first written to the stream. Whilst we were not able to gauge this information from the EventBridge Pipe, we were able to evaluate metric “Iterator Age” from the Lambda consumers.

Reviewing Consumer Iterator Age

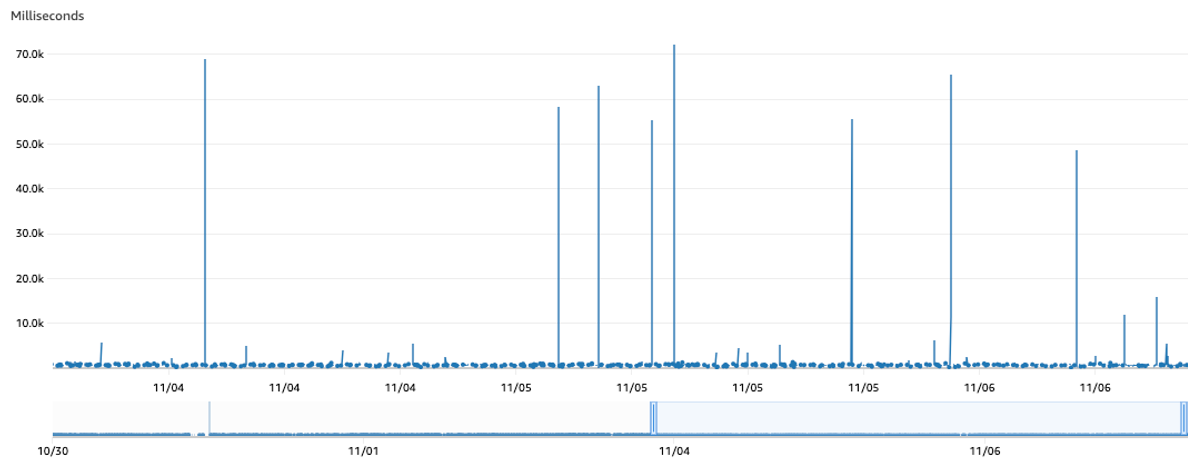

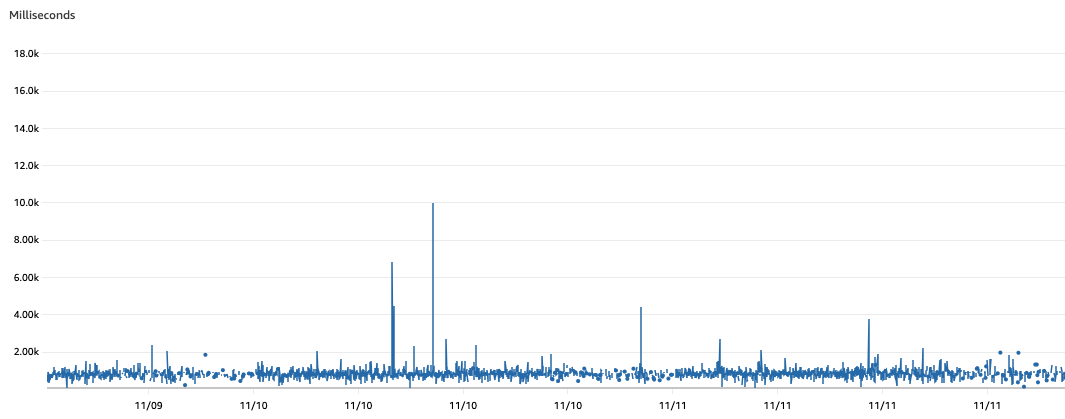

Focusing on one particular Lambda consumer, we learned that the average iterator age per minute frequently exceeded 50s over a two day interval.

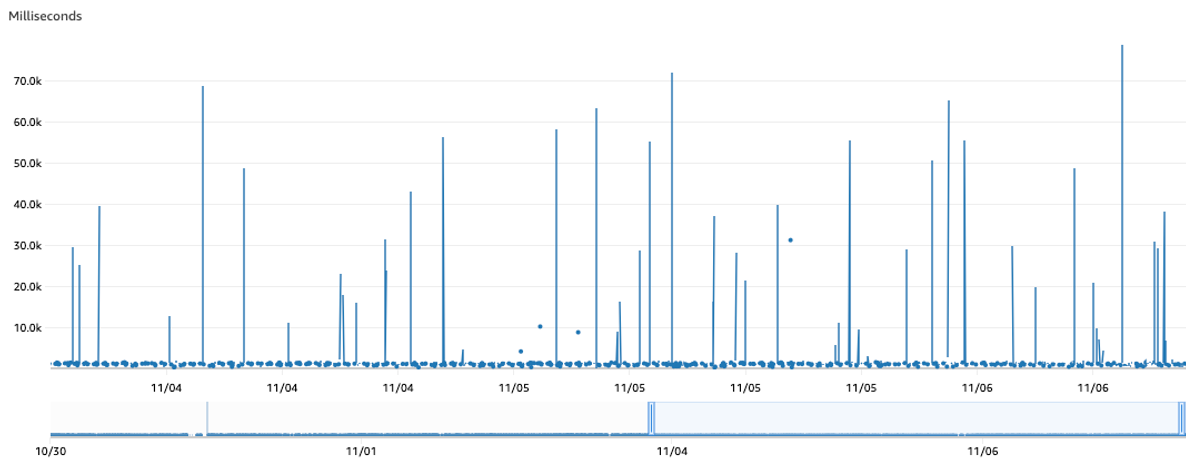

Similarly, we noticed the maximum iterator age per minute for the same consumer over the same interval would occasionally surpass 60s.

Based on these findings, we explored options to lower the iterator age and thus decrease the time it takes for services to successfully process records from the stream. In particular, we wanted to reduce the frequent spikes in average and maximum iterator ages observed.

Debugging High Consumer Iterator Ages

There were a few avenues to explore which may explain high iterator ages:

Consumer Processing Failures

Reviewing Lambda metric “Errors” for the DynamoDB consumers, we confirmed no errors were thrown during high iterator age intervals. Therefore we ruled out consumer retries as the likely cause of high iterator ages.

Low Consumer Throughput

Exploring consumer throughput, DynamoDB Streams offer configuration options for both EventBridge Pipes and Lambda functions worth highlighting which may improve performance:

- Batch size: how many records to read and process in a single execution of the consumer.

- Parallelization Factor: how many consumer instances should process records in parallel.

Therefore, to increase throughput, we explored an increase to the batch size and parallelization factor individually. However, alterations to these properties delivered no notable performance gains. Therefore we ruled out low throughput as a probable cause of high iterator ages.

Throttled Stream Read Requests

This leaves us with the possibility of throttled reads from our initial options. Assessing throttles proved more challenging: there’s no metric out-the-box from DynamoDB Streams to measure this. However, diving into AWS documentation, we learned the following:

“No more than two processes at most should be reading from the same stream’s shard at the same time. Having more than two readers per shard can result in throttling.”

Each shard is a grouping of records within the DynamoDB Stream. Given our stream had four consumers – twice the advised limit – potentially reading from the same shard at the same time, it’s likely our consumers were throttled. Further investigation was required to confirm this theory.

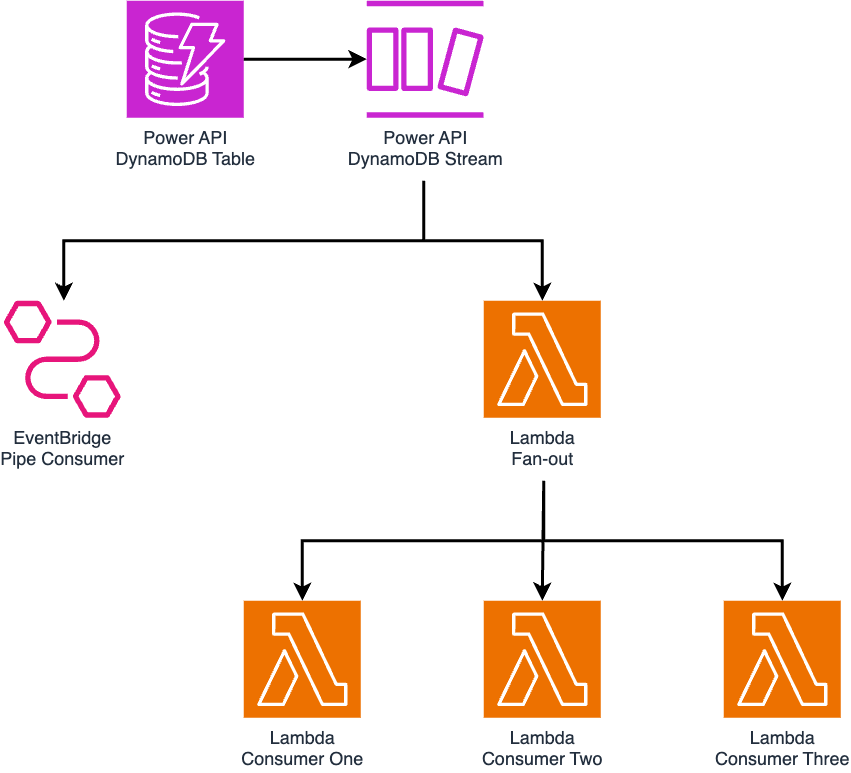

Introducing the Fan-Out Function

To reduce the Stream consumer count, we introduced a new Lambda function to the Power API architecture: a “fan-out” function, acting as a single Lambda consumer to route records to the other functions previously reading direct from the Stream. This reduced the consumer count from four to two: the EventBridge Pipe, and the Fan-Out Lambda function.

The Fan-Out function invoked the other functions synchronously: waiting until they all finished processing records so that any errors could be captured and managed in a single location, thereby leveraging automatic retries from the DynamoDB Stream integration.

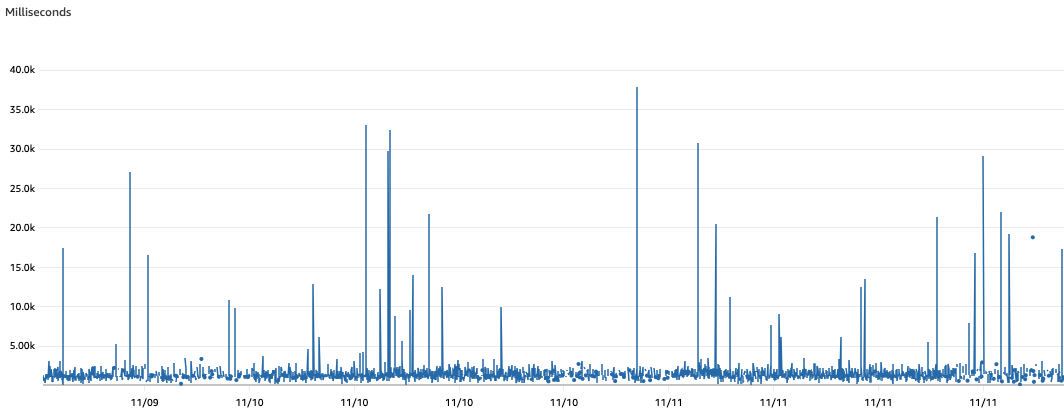

After finalizing our implementation of the Fan-Out function, we left changes to soak for a few days before reviewing the new function’s iterator age performance. Over the course of two days, we observed an average iterator age which occasionally breached 4s in the screenshot below, compared to the regular spike above 50s observed previously.

In addition to this, we saw the maximum iterator age peak just below 40s. This was a drop from the 70s threshold which was periodically breached before.

The notable drop in iterator age findings suggested our consumer count for DynamoDB Streams may explain a sizable share of observed iterator ages. However, we wanted to see if we could reduce iterator ages even further.

Since the Fan-Out function invoked all downstream functions synchronously, it would only take one slow function to impact Fan-Out processing times, thereby impacting the rate in which all subsequent records are read from the DynamoDB Stream. One of these downstream functions was notably slower than others to process records due to an API dependency elsewhere on the platform. We optimized this API to reduce record processing times, but these changes provided only limited improvement.

Furthermore, having a Fan-Out function introduced a new single point of failure in our architecture: if a bug were introduced to the Fan-Out function, or errors occurred in the underlying infrastructure, this would impact all three downstream functions. Therefore, we wanted to explore alternative strategies which would remove the added point of failure, whilst allowing consumers to read records concurrently, independent of each other’s processing times.

For our use case within Power API, we required a solution that supports at least four consumers reading from the stream in parallel. It didn’t matter whether records were processed in-order, nor did it matter if the streaming platform delivered duplicate copies of records. This is because all four consumers are idempotent: if the same record were received twice, consumers can gracefully process duplicate copies without any issues.

Migrating to a Kinesis Data Stream

Late in 2020, AWS rolled out an alternative stream integration for DynamoDB in the form of Kinesis Data Streams. This is a separate AWS managed streaming service which allows data producers to emit records for many consumers to process, exactly like DynamoDB Streams. However, there are a few notable differences worth calling out between these services.

DynamoDB

Kinesis

Consumer Limit

2

20

Data Retention Period

24 Hours

One Year

Records De-duplicated?

Yes

No

Record Ordering Guaranteed?

Yes

No

Given our solution was still fit for purpose under Kinesis’ offerings, we elected to replace DynamoDB Streams and the Fan-Out Function with a Kinesis Data Stream. Kinesis streams support two modes: on-demand and provisioned. An on-demand stream scales automatically to handle variable traffic volumes, whilst additional overhead is required to adjust a provisioned stream’s capacity if it’s unable to handle higher volumes of data.

Under Kinesis’ standard setup, all four consumers may leverage up to 2 MB/sec of shared read throughput. However, in cases where we want to improve performance for specific consumers further, we can apply Enhanced Fan-Out to deliver dedicated read throughput of 2 MB/sec per consumer.

For the Power platform, we set up an on-demand Kinesis stream with Enhanced Fan-Out for three of the four consumers. The final consumer is left to utilize shared throughput in isolation. Given no other consumers rely on shared throughput, this final consumer is effectively granted the same throughput as each Enhanced Fan-Out consumer.

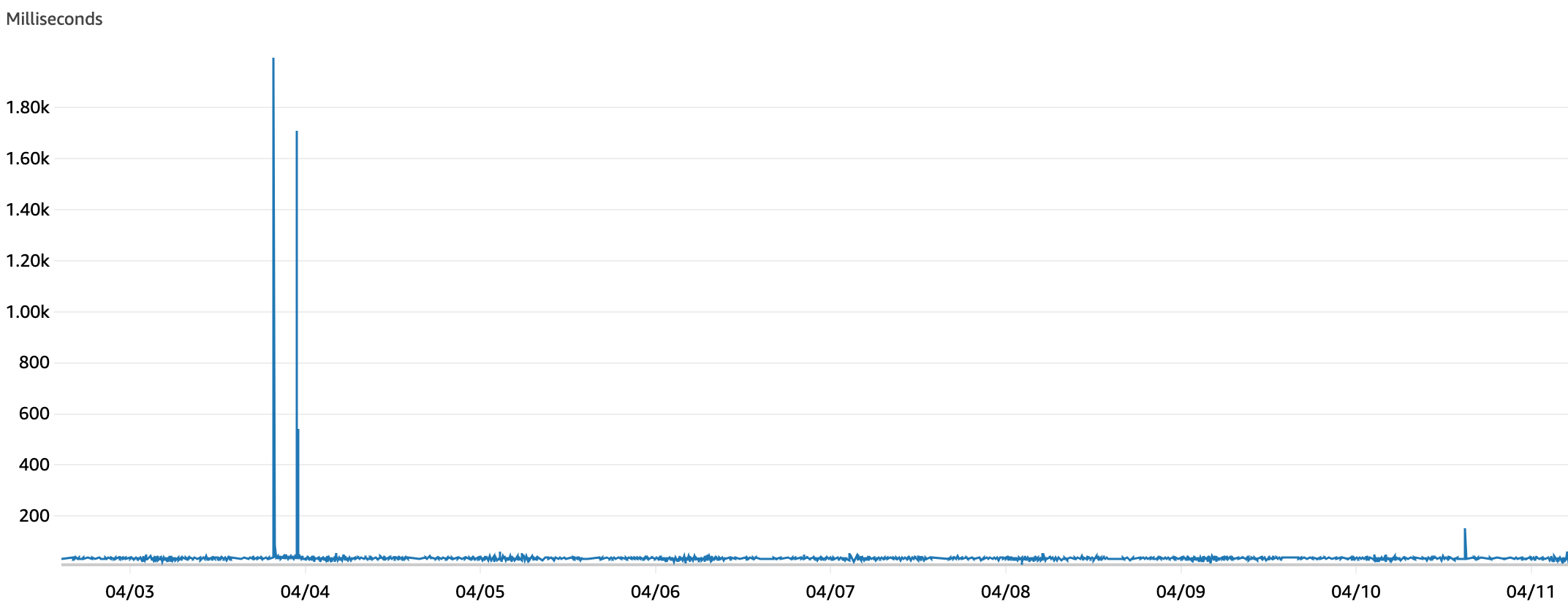

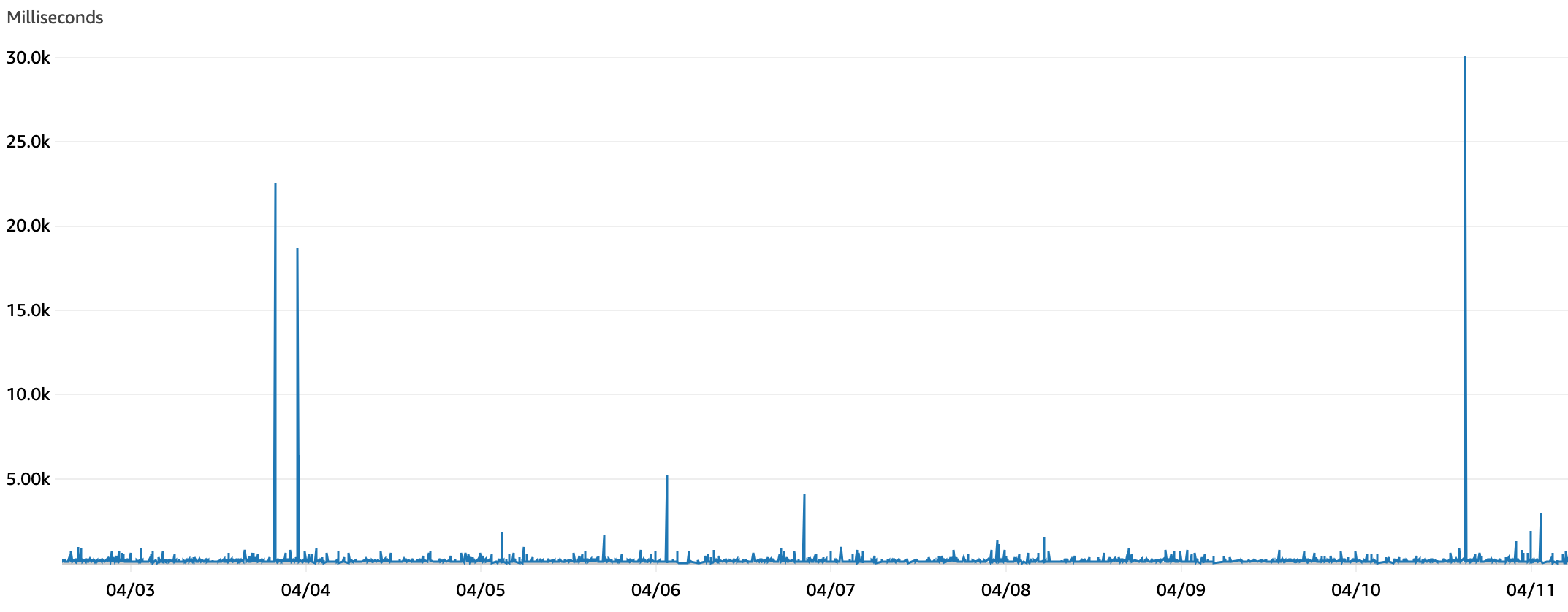

Under this new architecture, we reviewed our iterator age metrics once more and observed that the average iterator age over a one week period dropped to a worst-case scenario of 2s.

Furthermore, the maximum iterator age metric did cap at 30s, an improvement from the previously observed maximum of 40s. Iterator ages upward of 15s occurred rarely. Where higher ages occur, those are likely attributable to spikes in traffic or Lambda consumer timeouts.

The general drop in the iterator age was a significant win for the team. In summary, three changes of increasing complexity led to this improvement:

Cost Considerations

Whilst performance gains were our primary objective, it’s worthwhile briefly discussing cost implications when migrating from DynamoDB Streams to Kinesis. First, note how the EventBridge Pipe and Lambda consumers are charged to read data, which differs considerably between the two solutions.

DynamoDB

Kinesis

EventBridge Pipe

Charge after monthly quota.

Charged for all reads.

Lambda Function

No charge.

Charged for all reads.

Diverging further from the DynamoDB charge model, Kinesis costs include several factors worth highlighting which include

- the volume of ingress data written to the stream. The number of records put on the stream, as well as the size of each individual record, contributes toward costs.

- whether we use on-demand or provisioned stream capacity mode. We’re charged an hourly rate for each stream operating on-demand.

- the data retention period. We’re charged an “extended” rate for data stored beyond 24 hours, and a “long-term” rate for data persisted longer than seven days.

- how many Enhanced Fan-Out consumers were applied. Each Enhanced Fan-Out consumer incurs additional read charges for the dedicated read throughput received.

Given the API was handling increasing volumes of traffic throughout the migration process, it’s tricky to give a direct comparison of costs between the DynamoDB and Kinesis Stream architectures. Generally though, it’s expected that costs would increase after switching to Kinesis, so we advise reviewing AWS’ cost model and weighing up the possibility of greater costs against performance gains before committing to a migration.

What Next?

We’re satisfied with the performance improvements delivered in switching from DynamoDB Streams to Kinesis, whilst accepting an increase in costs doing so. If we wanted to reduce the iterator age further for Lambda consumers, we could explore a couple additional options:

We’ve learned a lot from the migration process to Kinesis Data Streams. In particular, how to manage this migration gracefully, whilst setting up suitable metrics to observe Kinesis stream performance. Stay tuned for further updates from us about the lessons learned, and how Kraken uses AWS elsewhere to solve problems in the energy sector.

Source:: Kraken Technologies